Car-parts molders steer course for success as market evolves

By Karen Hanna

The evolution of electric vehicles, along with the launch of about a half-dozen new automakers, is sending a charge through the industry. Suppliers say they have to be nimble to stay competitive.

For workers at the U.S. headquarters of Viking Plastics in Corry, Pa., molding, assembly and packing are old hat. As new companies seek partners, though, another role is emerging: teacher.

“As you look at the new players ... that are working to develop either full vehicles, like a Tesla, or the companies that are starting up to support them, to make electric motors to provide the autonomous vehicle componentry, a lot of them don’t have a lot of plastics experience when they’re designing. A lot of them understand metals better,” said Shawn Gross, Viking’s corporate engineering manager.

“For us, there is an educational component to our job where we are engaging a designer or program team at a potential customer and educating them on what plastics can truly do.”

It’s just one challenge in dealing with an automotiveindustry that’sin transition. As companies like Tesla try to establish markets, the traditional supply chain is becoming diluted and fractured, with more companies bringing out carsThe internal-combustion-engine platform that replaced the horse-and-buggy is itself set for obsolescence with the evolution of the electric vehicle. Manufacturers are increasingly turning their focus to entertainment and sensing features, and even driverless capabilities.

Faced with new pressures, companies like Viking are seeking to take on new tasks for their customers and prospective customers; to increase quality levels; and to wring greater value from everything they do.

They have no choice but to adapt, said Laurie Harbour, a manufacturing consultant. The president and CEO of Harbour Results, she works with a lot of mold makers, a group that can be resistant to change.

“ ‘Hey, we make tools this way, we’ve always made tools this way. Why would we ever do something different?’”Harbour said, echoing the comments she’s heard from clients in the industry. “And I’m telling them that you’ve got to start getting creative and innovative, because the cost structures that are in the industryReinvention becomes Job 1

Ontario-based Laval Tool began confronting the new realities more than 10 years ago. In the midst of the Great Recession that gripped the globe about a decade ago, it faced a choice: Ramp up or peter out.

Since then, it’s grown from about 20 workers in 2010 to 71 now. Once exclusively a maker of compression molds, it has vertically integrated to offer its customers an entire suite of services, from mold design to part production.

The transformation has better equipped it to deal with evolving customer needs and tightening competition, company President and CEO Jonathon Azzopardi said.

“What we’re trying to do is we’re trying to value-add where we can, charge where we can, while still satisfying our clients,” he said. “So, for instance, theLaval, which makes full-run parts and provides engineering services, has begun serving what Azzopardi calls the “mobility market.” He draws a distinction from the automotive market because the players and their needs are so different.

The change is cultural, as much as technological.

“It’s broken free of the knowledge of the traditional automotive space, right?” he said.

Laval supplies parts to Waymo, Google’s self-driving technology company. If you live in Arizona, you might have seen Waymo’s self-driving fleet: modified Toyota Priuses, Lexus SUVs, a custom-built prototype and fully autonomous Chrysler Pacifica hybrid minivans. The rollout continues.

“People say, ‘That’s new technology.’ It is somewhat new technology,” Azzopardi said. “But it’s also a different culture, too. They don’t have the same cycles as the automotive [manufacturers], they don’t have the same engineers, they don’t have the same agenda.”

Such companies represent new business opportunities, but because they’re starting from scratch, they order in smaller volumes than their more established competitors. And, in many cases, they don’t know the possibilities of plastics.

“The basics aren’t there. They’re doing a lot of trial and error. And we’re having to support them from a design standpoint a lot more than we would with a traditional OEM,” Azzopardi said.

These needs, combined with the smaller volumes, add up for suppliers like Laval.

“Us, as a supply chain, we’re being asked to do so much more than what we used to do, which is fine, as long as you can get paid for it and you can do it profitably. We’re happy to do that,” Azzopardi said. “But in some cases, that’s not the case. You’ve got to try and manage, vertically integrating your company, to try to best service your clients.”

Value-added proposition

Viking, for example, has added engineers to work with customers on issues involving manufacturability and resin selection. It has also invested in more metrology equipment.

“In the last few years, the programs have gotten bigger, with more technology required in our plant. It’s more than just building the mold and making parts; we’re doing other things to those parts. So those investments have had to come along with it,” said Gross, who has worked at the company about 14 years.

With facilities in four countries, the company relies on the automotive industry for about 85 percent of its work. Customers of the Pennsylvania plant include the traditional automakers, some of the new players and a variety of auto-parts suppliers; Jeep sources some components for its hybrid vehicle from the facility.

Sealing components for sensitive systems, such as vehicles’ heating, ventilation and air-conditioning systems, are a specialty at Viking’s Corry facility — and one reason why it has put even more investment into precision.

“If you pop the hood of your vehicle and look for where they would put the refrigerant in, more than likely it’s a Viking cap,” Gross said.

Such seals require tight tolerances and often involve plastic-over-metal brackets that can absorb high pressures.

As car manufacturers add sensors to vehicles, there’s a lot more riding on these sorts of components. While such parts once played a role in keeping an internal-combustion engine from overheating, now they’re also securing sensors on vehicles that are doing at least part of the driving themselves.

“When you think about a radar system on a vehicle, it has to be precision so that it’s pointing in the right direction and not vibrating out of position, so that the radar that tells you that a vehicle in front of you is stopped, it tells your vehicle, ‘You need to be braking now,’ ” Gross said.

Electrifying changes

The evolution of vehicles from human-operated to sensor-driven, from internal combustion to battery-powered, creates urgency for Viking to continue to refine its processes.

Finding corollaries between the work it has done in the past and the work automakers might require in the future is one way it stays competitive.

Some current parts will have parallels in the future; others will become obsolete.

One area of emphasis continues to be weight reduction. As car companies look to extend the range of batteries for electric vehicles, it could become even more important.

“Something that we do highlight ... is helping a customer look at their portfolio of metal components that go on a vehicle and being able to give them some ideas on where we could lightweight,” Gross said. “We’ve done several steering systems that are going into GM and Ford vehicles where things that were cast and machined are now injection molded.”

Viking’s 100-person-plus team in Corry is trained to adapt, he said.

“We’ve groomed our entire team around the idea that things are going to be more complex. And the quality requirements are always going to be very stringent, right? They don’t want any defects. And in fact, instead of in the past where, [if] you send a defect, you might get a slap on the hand and have to sort parts, some of these are becoming safety-critical elements,” Gross said.

Emphasis on quality

Like Viking and Laval, custom molder Acromatic Plastics also has a diversified portfolio. With a Class 100,000 clean room and offerings that include welding, assembly and 3-D printing for prototyping, the company serves a variety of clients in the industrial, medical and military sectors.

“We’re happy to have all types of high-tech companies,” said George Doumani, VP of sales and engineering.

As the company works to stay competitive, automation and quality are important differentiators.

Doumani said Acromatic began supplying parts for the automotive industry prior to 1991, when he joined the company. It has 12 hydraulic Kawaguchi and Nissei injection molding machines, with clamping forces ranging from 66 tons to 720 tons, and it is considering purchasing three more, to bring capacity up to 1,100 tons of clamping force.

Thirty-two people are split over three shifts a day, five days a week, and the company is considering hiring a few more.

A key to staying cost-competitive is automation, Doumani said.

“We have robots on all the machines, and most of the tools that we like to get involved with are designed to run automatic, so the robots can do most of the work. Obviously, everybody’s trying to keep their workforce as small as possible because of all the costs associated with each person. If you look at the cost of the benefits, everybody knows the situation with medical insurance. You know, the fewer people, the better.”

“Whether it’s a robot loading and unloading an injection molding machine, applying, repeatedly, an adhesive bead to bond two plastic parts together, or automatically stacking your finished products into shipping containers, the business case in 2021 is easily made for inclusion of robots in many plastic parts making facilities,” Dueweke said.

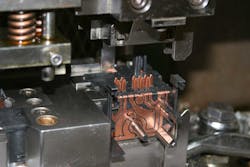

Acromatic’s products include small electrical connectors for the automotive industry. While it isn’t working with electric vehicle makers yet, the company isn’t ruling out the possibility.

“I’m sure because of our work with connectors, there will probably be more opportunities for us,” Doumani said. “We’ve also been contacted by some companies regarding fuel cells, and those are larger parts. So, we’ve seen some activity in that area. We probably will have some opportunities to quote on those.”

Like other molders, Doumani said he won’t — and can’t — compete solely on price.

“We prefer to work with customers who are really interested in a quality part,” he said. “We don’t go chasing every piece of business. We have a certain way of operating and [a way] we like to work. We’ve got a very good quality organization and you know there’s costs associated.”

Equipped for the challenge

The demand for metrology services attests to the precision customers are requiring. Quality remains a strong selling point.

With ever-tightening requirements for precision, molders might need to 3-D scan parts or overlay CAD drawings to be sure they’re molding within specs, Viking’s Gross said.

“It’s not just a simple plastic part, not to minimize what’s been done in the past, but … we see more dimensioning schemes where people have tighter requirements around profiles and things of that nature that require more sophisticated metrology. … You can’t just use calipers and micrometers; you’ve got to use the CMM,” he said.

Besides adding to its roster of engineers, the Corry plant provides regular training, including RJG training, to its workers; some employees have attended American Injection Molding Institute Training.

“If you're doing more than shoot-and-ship, if you're doing value-added componentry like we are, [you’ve] had to really raise the technical capabilities of the entire team,” Gross said.

Meanwhile, in Ontario, Laval continues its own transformation.

Offering more services while maintaining part quality could give some molders an edge an ever-more competitive market.

“You’re going to see that the companies who don’t want to adapt and change are going to fade away because they’re no longer going to be needed the same as a guy who does it all,” Laval’s Azzopardi said.

Karen Hanna, associate editor

Contact:

Acromatic Plastics, Leominster, Mass., 978-537-4102, www.acromaticplastics.com

Fanuc America, Rochester Hills, Mich., 248-377-7000, www.fanuc.com/locations/america.html

Harbour Results Inc., Southfield, Mich., 248-552-8400, https://harbourresults.com

Laval Tool, Tecumseh, Ontario, 519-737-1323, www.lavaltool.net

Viking Plastics, Corry, Pa., 814-664-8671, www.vikingplastics.com

Related stories:

The electric vehicle revolution opens doors for plastics, say industry experts.

Pressure is mounting for mold makers to adapt.

3-D printers carve out niche in automotive marketing.

Changing designs create opportunities for injection molding machinery makers.

Ron Shinn: Electric vehicles are different, so processors need to adapt.

Hot runners inject new options for making tough automotive parts.

About the Author

Karen Hanna

Senior Staff Reporter

Senior Staff Reporter Karen Hanna covers injection molding, molds and tooling, processors, workforce and other topics, and writes features including In Other Words and Problem Solved for Plastics Machinery & Manufacturing, Plastics Recycling and The Journal of Blow Molding. She has more than 15 years of experience in daily and magazine journalism.