West Michigan Molding touts Chinese vertical presses

The artwork displayed on a stainless steel table inside this factory is a sight to behold. It is not a piece that would hang on the wall or ever be displayed in a museum, unless the museum was for molds and tooling.

"It's kind of impressive," says Terry Kozanecki, executive VP of West Michigan Molding Inc. (WMM), a custom injection molder in Grand Haven, Mich. "I've never seen 28 valve gates, but this one has it. You would not have seen this on a tool five to 10 years ago."

One half of this two-cavity mold sits on the table; the other half is nearby as the total package is prepped to go for testing at Wittmann Battenfeld in Torrington, Conn. Wittmann is supplying the Cartesian robot for WMM's latest cell. The robot is a W832 with XYZC axes with a high-torque, C-axis rotation for placing. An outside vendor built the mold, and WMM's in-house technician is getting the mold to a point of easy setup.

Once the trials are done, the mold and robot will come back to WMM and join an all-electric 450-ton Haitian injection molding machine to mold seat springs that will be supplied to WMM's automotive customers. WMM, a General Motors supplier, achieved zero defects per million parts last year.

"This will run in a horizontal and they will preload the wires robotically," says Kozanecki. "This will be our first attempt at running one of the wire tools in a horizontal machine."

By using a horizontal press, officials are trying to reduce the manpower requirements. Using automation on that cell also will reduce cycle times.

"One of the things we can do is try to attempt to take some of the labor out. Instead of a 28-second cycle for one part, we're attempting to do two parts in 30 seconds," says program manager Kevin Wierda.

This process is not completely new in the industry, but it is new for WMM. One other company is doing it a little bit differently by going in from the side to insert the wires. WMM's process comes in from the top. The other company is doing it on a 30-second cycle. WMM is confident it can, too.

WMM uses vertical/vertical injection presses to mold these seat springs. These machines are designed with open clamps and rotary tables, so they can work with multiple molds and simultaneous operations. One of the main advantages is that tools from horizontal presses are transferrable and do not require a manifold.

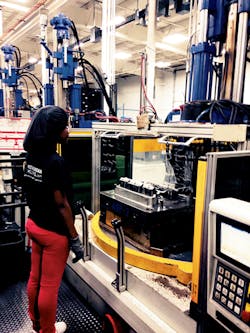

Inside WMM's factory, five vertical/vertical 285-ton injection molding machines from Chinese manufacturer Multitech Machinery Ltd. are operating, all dedicated to the same application. Four of the presses run PP, injecting it around the wires. The other press runs nylon. A worker, who has climbed stairs to reach the two-story machine's top level, manually places the wires in the molds while the machine is injecting the plastic behind it. A load-assist arm helps the wire stay in place.

WMM officials were motivated to get into vertical/vertical when a local customer came to them with the wires and wanted the plastic injected around the wires. It makes the most sense for this product, officials say.

The week before Plastic Machinery Magazine's visit, officials had equipped each vertical/vertical press with a light. If the machine is off cycle or not running, the light turns red. If the press is running on cycle, the light will be green. This is one of the tactics used by the company to avoid operating issues.

"Anybody can walk by here and say, 'OK, the press is running on cycle,' " says operations manager C.B. Long.

The company's focus has been to equip its machines with robots or parts pickers. Every time the company buys a machine, it buys a robot or parts picker with it. Fifty-seven presses with up to 1,800 tons of clamping force operate in 186,000 feet of manufacturing space.

Kozanecki is very blunt about the choice of Chinese injection presses. The factory still operates Van Dorn and Cincinnati presses, but it purchases new presses from Chinese manufacturers. Cross-functional teams make decisions about equipment and machinery purchases.

"People ask why we buy Chinese. They're half the price!" he says. "They have American pumps and motors and parts on them. Like everybody told us on the vertical, 'Five years from now, they're going to be junk.' But I'm still running them. Five years later, they are still running and they're making parts."

Homegrown technology with particular machinery choices

WMM is pushing technology boundaries for continuous improvement. Most of its technology is homegrown.

WMM, which was previously known as Grand Haven Plastics, changed its name in 2012, after Marcia Steele became its owner and CEO.

Steele is hands-off at WMM, leaving day-to-day operations to Kozanecki and the management team. She also owns HS Die & Engineering Inc., Grand Rapids, Mich., which is where she makes her headquarters. HS Die supplies tools to WMM. WMM builds some small tools itself and has one tool and die maker and an apprentice mold maker on staff who performs the preventive maintenance.

WMM is certified woman-owned, an imperative in doing business with automotive customers because there are additional incentives. The company holds a certification from the Women's Business Enterprise National Council.

"Does it get us in the door? I don't know. It keeps us there," says Kozanecki.

Currently, 80 percent of sales come from the automotive industry, and Kozanecki doesn't see a need to change that.

"Cars still drive this country," he says. "And we want to be a part of that."

The remaining business comes from markets like pet products and outdoor watersports. For complex products like kayak paddles, WMM has to maintain machine flexibility for color changeovers because these parts have to be molded in different colors. Sometimes there are multiple colors in one part to achieve effects like swirling. These situations require different melt temperatures for different colored resins.

Streamlining through lean principles, expanding assembly

Lean manufacturing is a must here, especially when supplying the automotive market. You hear the words kaizen and poka-yokes as the management team chats during the tour.

Kaizen is the philosophy of continuous improvement, while poka-yokes are the tools or systems put in place to avoid human error, like the green and red lights on the vertical/verticals. Such tools and systems have been implemented throughout the plant. One significant educational tool being used is video programs on the presses for training. That is augmented by paper manuals at the press.

"Besides telling the operator how to do it and having all the paperwork to show the operator how to do it, we also have a video program in case they question something or they don't remember what to do," says quality manager Ken Byrne.

A cell leader supervises each group that works on one press; the leaders are more knowledgeable about that particular area and wear orange to differentiate them from other employees. The plant operates on closed-loop process control. Under a system from RJG Inc., WMM sends its process engineers to Grand Rapids Community College for a master molder program.

Mold setup is coordinated by special carts that are motorized and hold all the necessary supplies for mold changes. Employees drive a cart up to a press and can perform the mold changeovers much more quickly.

"Being a custom molder, we're shuttling molds every two days, every two hours, whatever. Everything they need is right on the cart. Instead of walking away to get things, it's all right here," says Wierda.

WMM is performing more secondary operations and has achieved efficiencies by shifting those tasks from the injection molding cells. Officials are expanding the assembly area because they are moving secondary operations away from the presses. Key secondary operations include painting and welding, including vibration welding. WMM paints 33 parts for the Corvette. The interior of the Corvette requires soft-touch paint.

From a staffing perspective, it makes sense to pull away those secondary operations and have a trained team that understands one specific area. This in fact helps to optimize the molding process. Cycle times are affected when secondary operations are included, and if there is a learning curve for a person to get through the secondary operations, the entire cycle could take 100 seconds.

"Do we optimize the press and bring it over to an area where that cycle time isn't as important?" asks Long. "Once that learning curve is back in place, we haven't lost capacity in the process."

Angie DeRosa, managing editor

Contact:

West Michigan Molding Inc., 616-846-4950, www.wmmolding.com