Tri-Mack innovates to create thinner deep-draw parts from thermoplastic tapes

By Karen Hanna

The rise of drones and electric vehicles (EVs), along with demand for more-sustainable materials, is driving an impulse toward innovation for one processor with deep ties to the aerospace industry.

At Tri-Mack Plastics Manufacturing Corp., Bristol, R.I., thin is in.

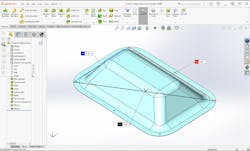

But the model for body shape, in this case, isn’t Twiggy. It’s a deep-draw part made from stacks of unidirectional thermoplastic composite (TPC) tapes — heated in an infrared oven and stamped into shape for use as enclosures that, along with a function layer, can block electromagnetic interference (EMI).

“We had made a relatively deep-draw part for a customer a couple of years ago, and that was sort of our basis for it,” Kain said. “We're sitting around, saying, ‘Well, how deep do you think we can go?’ We decided that we could really go for it and go as deep as we think is possible, or we could be conservative and make sure we get something for the show.”

A team, led by Ben Lamm, applications engineer for composite materials and processes, took the moonshot approach. Tri-Mack, whose 120 employees perform injection molding and secondary processes, in addition to layup, now is seeking to improve on the thresholds it set at CAMX — where it showed eight-ply layups that were only 0.04-inch thick. Since then, it’s made production parts that use four plies of tape and measure just 0.2-inch thick.

The company uses tapes from carbon-fiber-reinforced composites, as well as several different base resins, including polyaryletherketone, polyether ether ketone and polyetherimide.

Exactly how the team slimmed down so much is proprietary.

“I can't tell you much about our special sauce, but it comes down to the way we designed our tooling, and the material handling system that we're using,” Lamm said.

Thanks to the company’s focus on thinner laminate, Tri-Mack can make parts more quickly, with less material and lower costs. EMIs made from the layup would contribute less weight to vehicles, so they’re less of a drag on fuel economy. And, unlike thermosets, thermoplastics are recyclable.

In a press release, Tom Kneath, VP for sales and marketing, summarized the advantages:

“Where strength and durability are priorities in addition to the lightest weight, continuous-fiber TPCs are the material of choice. It is less brittle than thermosets, delivers 10 times the strength of injection-molded parts and, with our enclosure, provides a 30 percent weight reduction versus 6061 aluminum,” he said.

The company’s new manufacturing process for enclosures allows it to embed EMI shielding or add localized reinforcement, without the use of metal or the need for plating or painting.

“With this TPC enclosure, we can eliminate that secondary process because, as we're laying up the base material, we can incorporate a layer of material that's designed for that EMI shielding purpose,” Lamm said.

“One of the things [with] that thermoplastic composite, the real advantage, and that our customers are starting to zero in on is, the cycle time,” Kain said.

While thermoset composites have to be stored frozen, then thawed, Tri-Mack's thermoplastic versions are designed for efficiency, requiring no hand layup or other manual processes. The deep-draw shapes can be formed in minutes — a significant upgrade over the post-curing cycles required for thermosets, which are often set in autoclaves.

Lamm said Tri-Mack's vertical integration, from part development to delivery, has allowed the company to hone its processes to make thinner tapes, but the evolution — spanning 5 to 10 years — hasn't been without challenges.

“One of the primary challenges in making a deep-draw part like this out of unidirectional material is preventing wrinkles; the material will tend to want to wrinkle, the fibers don’t want to stay straight,” he said.

Not only does that compromise the functionality of the part, it can hurt the part’s overall look.

But Tri-Mack has overcome those issues, Lamm said.

“The way that we tension the fibers during the forming process has resulted in a largely wrinkle-free part,” he said.

The process results in fibers that are all oriented the same way, rather than folding upon themselves.

“Unidirectional [fiber orientation] is kind of the top of the food chain; that's where you're getting the most mileage out of the fibers because they're already straight,” Kain said.

Tri-Mack's innovative efforts come at a time when two industries — aerospace and car manufacturing—are undergoing rapid change that has accelerated demand for EMI shields. Critical technologies in EVs are vulnerable to EMI, and airplanes — always at risk from EMI, which can damage electronics or interfere with their function — have suddenly become accessible to many markets, with the arrival of drones.

It’s why Kain is predicting booming demand for one of his company’s signature products.

“They have Tri-Mack parts on almost everything you see flying,” he said. “It’s fun to think about.”

At the show, drone and EV makers showed significant interest in Tri-Mack's EMI enclosures, he said. They’re looking to scale up, as their end products transition from niche to ubiquitous.

“You get into an application where they're seeing rapid growth, like in the EV or drone market, where they're saying, ‘We need to get 50 of these things qualified, but two years from now, we're going to need 20,000 of these things,’ ” he said. “There's no way the traditional thermoset industry is going to be able to support that.”

Karen Hanna, senior staff reporter

Karen Hanna | Senior Staff Reporter

Senior Staff Reporter Karen Hanna covers injection molding, molds and tooling, processors, workforce and other topics, and writes features including In Other Words and Problem Solved for Plastics Machinery & Manufacturing, Plastics Recycling and The Journal of Blow Molding. She has more than 15 years of experience in daily and magazine journalism.