Machine design helps molders achieve sustainability goals

With brand owners and packaging makers under pressure to adopt greener practices, machinery suppliers must take stock of the role they can play in enhancing recyclability and increasing the use of new bio-based resins.

For Michael Sansoucy, Arburg’s director of packaging, sales and applications, it begins with machine design. But true change will take the entire supply chain.

“It’s hard for us to go to a customer and say, ‘I will help you become more environmentally aware,’ if we’re not doing that ourselves first,” said Sansoucy, one of the speakers at the Plastics Industry Association’s Plastics Packaging Summit, scheduled for Nov. 3-5.

Recyclers’ Holy Grail

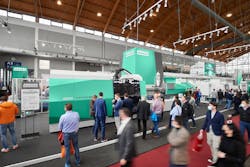

On the eve of Fakuma in early October, Sansoucy was in Germany looking forward to talking to customers about Arburg’s involvement in the HolyGrail 2.0 project, a collaborative effort among a variety of players, including Procter & Gamble and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, to find ways to more efficiently recover recyclable materials from the waste stream.

The project uses digital watermarks to tag recyclable packaging, which is where Arburg comes in — at Fakuma, one of its machines worked in concert with in-mold labels from MCC Verstraete in-mold labeling automation from Capetella to make cups and lids from recycled PP.

“So, you have a label on the cups and lids, and behind the label print is, in essence, an entire bar code that surrounds all of the product. … It’s a code printed into the label, so that no matter what shape that container is, as it goes down the recycling line, the camera can scan it and say ‘that's polypropylene, put it over there.’ … Even if the product is torn, crumpled up, somehow damaged, because it encompasses the whole part, it can still identify that product,” Sansoucy said.

He’s hoping that standardization of sorting methods will increase recovery rates.

"If this gets widely adopted, we can kind of keep that single-stream recycling going on, or at least be able to identify what’s polypropylene, what’s polyethylene, what’s PET, etc., without having to use other means, such as hand sorting, floating, etc."

Material challenges

But planning for products’ end of life isn’t Arburg’s only role in sustainability efforts. Sansoucy also stressed the OEM’s efforts to improve how its injection molding machines (IMMs) handle recycled and bio-based materials and increase the machines’ energy efficiency.

Recycled materials have different viscosities than virgin resins, while bioplastics have much lower melt-flow indices than comparable conventional resins. Greater machine control can help operators compensate for the variances, Sansoucy said.

Arburg’s process control system allows a user to adjust how the machine ramps up the fill rate; the system’s PressurePilot function can automatically adjust the ramp-up for transitioning from fill to hold pressure. This is suitable for many materials, including blends of PCR.

“That means I get a much more stable process regardless of my material viscosity,” Sansoucy said.

The benefit is more-even shots, sparing resin that could otherwise be overfilled, said Sansoucy, who provided the example of a 96-cavity tool for caps. Even a little overfilling of caps in the center of the tool can prove costly over the long run, he said.

“When I’ve got tight, tight margins, if I’ve got a portion of those cavities that are, let’s say, a tenth of a gram heavier, running that tool at a 2.5-, 3-second cycle time over the course of a year, you’re talking about thousands of dollars of resin that I potentially gave away,” he said.

In contrast, molders using bio-resins can experience problems filling parts.

“Normally, when I inject really fast, I hit a point where I’m pressure-limited. Now, I can’t push the material anymore; I’m going to get a short shot,” Sansoucy said. “But, if I can control that injection better, fill it quickly, but also play along with what that ramp is, I can make sure I don’t put the machine at its limit before the part is full.”

Greener machines

Arburg also is addressing calls for sustainability where the process starts — with its IMMs. Sansoucy emphasized that Arburg has ditched hydraulics where it can, and made them more efficient where they’re essential. It’s also developed or adopted more efficient drives, motors and water-cooling.

“I think making the machine as green as possible is key,” he said.

What happens outside the plant, though, is just as important, with recycling rates lagging far behind targets.

However, he said, chemically recycling resin offers the promise of recycled materials with virgin resin-type qualities.

"In all cases, the consumer needs to know that recycled material makes a good part that has the properties the consumer needs. If the material is mechanically recycled, the color choice maybe be limited to darker colors as it is hard to get all white material, he said. “However, if you consider chemical recycling, the ability to have bright colors and even clear material is possible.”

At Fakuma, Arburg ran a clear PP produced from chemically recycled material.

Sansoucy believes change — both inside the plastics industry and outside it — is coming.

“If we don’t find a way, governments and such will mandate it to happen, so we can either be in control of our destiny, or have it controlled for us. So, I think the industry as a whole needs to step up,” he said.

Arburg recognizes its role.

“We are also part of the solution to the problem. It’s not just the brand owner, it’s not just the resin supplier, it’s everybody that touches that material,” he said. “And, as a machine supplier, we take that very seriously.”

Twenty-nine years into a career in plastics, Sansoucy wants to believe in a future that doesn’t include talk of ocean plastics.

Is there a better path forward?

“Gosh, I hope so,” he said.

Karen Hanna, senior staff reporter

Contact:

Arburg Inc., Rocky Hill, Conn., 860-667-6500, www.arburg.com